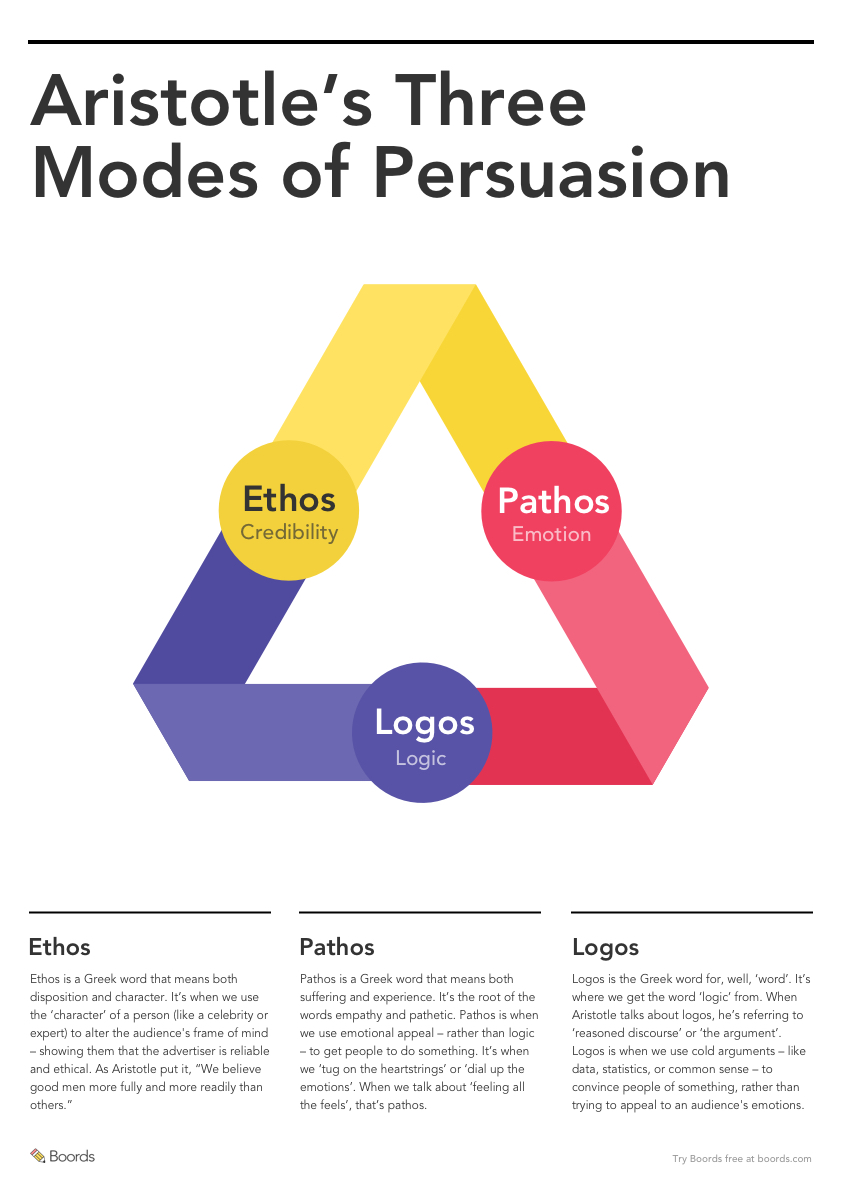

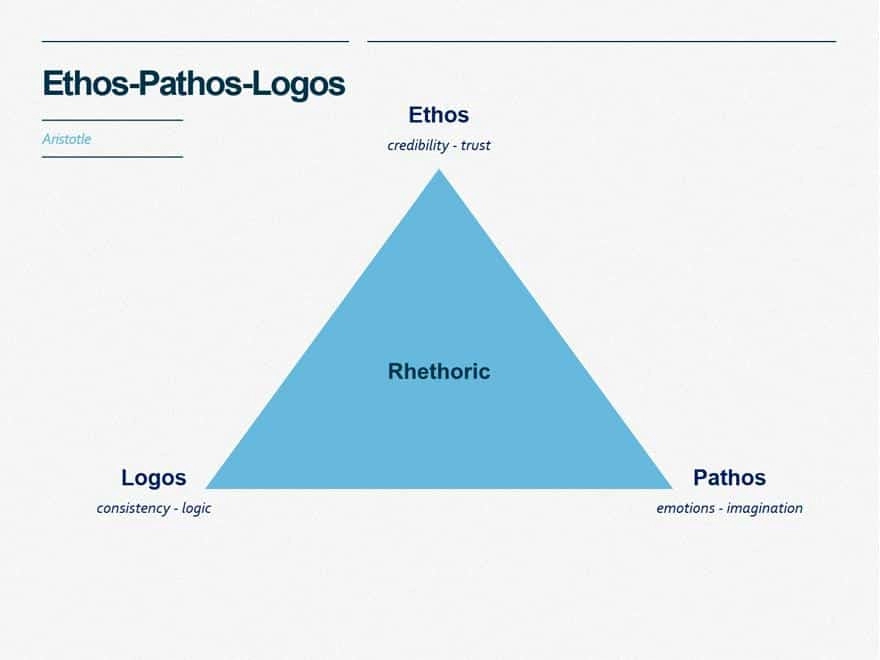

The very ordinariness of rhetoric is the single most important tool for teachers to use to help students understand its dynamics and practice them,” according to a paper by The College Board. “We employ rhetoric whether we’re conscious of it or not, but becoming conscious of how rhetoric works can transform speaking, reading, and writing, making us more successful and able communicators and more discerning audiences. And if your arguments are overly emotional rather than factual, you could lose your credibility. By the same token, if you only present the cold, hard facts, you could quickly lose students’ attention. In academia, logos and ethos-reasoning and authority-tend to be given more weight than pathos: an academic paper based primarily on pathos, for example, probably wouldn’t be taken seriously. To persuade an audience, we typically use a combination of the three rhetorical appeals. (It’s not about the emotion you are feeling, but what emotions you are evoking in others). If you can make students feel an emotion, or appeal to their sense of identity, you’re using pathos. Pathos (παθος) is the use of ‘pathetic appeal,’ which in Aristotle’s time meant appealing to people’s emotions or sense of identity. As an instructor, you likely have some inherent Ethos, but you could also draw on the ethos of others, such as citing results from a research paper. Ethos (ηθος) is the use of ‘ethics’ - which, unlike our modern usage of the word, refers to your credibility or authority on a subject.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)